Csernus started his career in the mid-1950s, with portraits and landscapes in a post-impressionist mood, which were informed by the influence of the style of his mentor, Aurél Bernáth. After his 1957 trip to Paris, the elements that referred to natural reality often dissolved in the expressive fabric of the painting that was woven with broad gestures. His new style did not find favour with the cultural authorities, while by the early 1960s a whole group of young painters had flocked under his banner.

When he and his artist wife, Katalin Sylvester settled in Paris in 1964, he produced book illustrations to make a living. His friends introduced him to several publishers, and he soon became an in-demand illustrator—Albert Camus, for instance, insisted that he contribute to his books. Csernus continued to make book illustrations even as a successful painter, which showed it was more than a source of livelihood. The designs provided an opportunity for experimentation, and the motifs that emerged would also be used in his paintings.

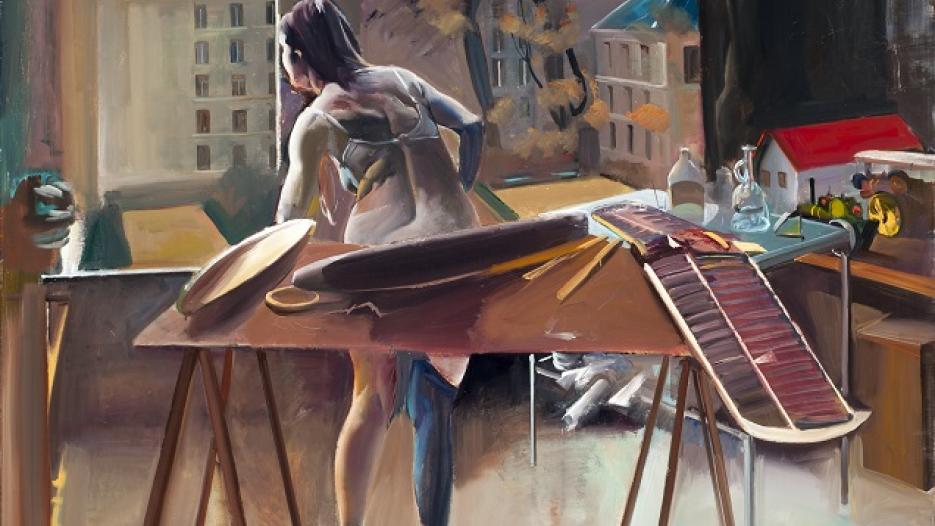

In the 1970s he turned to hyperrealistic representation: the scenes that take place in streets, marketplaces, at box matches, in suburban housing developments, or in his own studio, place the emphasis not on the subject but the bravura mode of painting. With Csernus, hyperrealistic representation does not equal a fastidious mode of painting; chiaroscuro, which communicates emotions, and the relaxed, effortless brushwork also play an important part. He could not—nor did he want to—become a complete devotee of photorealism; his brilliance as a painter destined him for more. In the late 1970s he began to paint nudes, and the portrayal of the naked body led him to a rediscovery of classical values. As he put it in an interview: “I was growing tired of painting all those creases.”

In the 1980s he drew inspiration from two great masters of the 17th century, Caravaggio and Velázquez, painting “faux-academic” biblical and mythological scenes, as well as still lifes, in their style. In efforts made at evoking and reconsidering one or another composition by some great predecessor, human figures started to appear in his Caravaggesque paintings, initially as the parts of still lifes, and then on their own. The nudes first began to move, then interacted, and finally formed groups for mythological scenes. Csernus frequently reinterpreted the available stories, and adapted the modes of presentation to the modern taste. The monumental figures, whose bodies are modelled with powerful light-shadow effects, tower like statues in the confined spaces, which are furnished like stages.

From the 1990s on he slowly returned to his immediate milieu, the compelling world of the Montmartre. This liberation of his craft also brought new subjects, with the inspiration of William Hogarth’s 18th-century series of engravings, The Harlot’s Progress, providing the focal points, and modern-day Paris furnishing the settings. He first made hundreds of studies for the series of seven paintings, then painted each scene in oil, before he began the final compositions. He was interested in the movements in a scene, the possibilities of representing groups—the story itself was needed only as a starting point. The works of this period embrace their relationship both to the history of painting and to contemporary reality, performing a truly individual revision and update of the tradition.

In the last period of his life, Csernus adapted Edgar Allan Poe’s mystical short stories to canvas; in these, the dramatic effect is intensified by the loose, almost extempore mode of painting. While he made several variations on a scene he had chosen, often he himself is the sole subject of the investigation: he studies his own features as he faces himself—and the viewer. Now little more than a sketch, now carefully worked out, these self-portraits help us to understand that Csernus extended reality to include his own painterly universe, blurring the boundaries of imagination and the real world.

Though they are not precedents to other works, drawings of his own studio fulfil a role in the artist’s oeuvre similar to that of the studies. The representation of the studio has a long tradition in art: it is the alchemist’s laboratory where reality mixes with imagination, giving rise to the artist’s visual universe—the place where aeroplane models blend easily with live models and bizarre guests.