With regard to its artistic quality, the painting of Lajos Gulácsy (1882–1932) is the equal of the work of those two other iconic artists of the turn of the century, József Rippl-Rónai and Tivadar Csontváry Koszta; like the latter, he too reinterpreted the concept of the “image,” but his character, his approach to the image, and the components of his art make him completely unlike the other two. We must also point out that his worth notwithstanding, his reception lags far behind the acknowledgement Rippl-Rónai or Csontváry has earned. Nor is this contradicted by the cult surrounding him, which usually draws on his tragic life, and not a recognition of his artistic values. It is true that his art in not easily accessible, and rather than making for fast experiences, the paintings benefit from an intimate, intensive and sensitive approach on the part of the viewer.

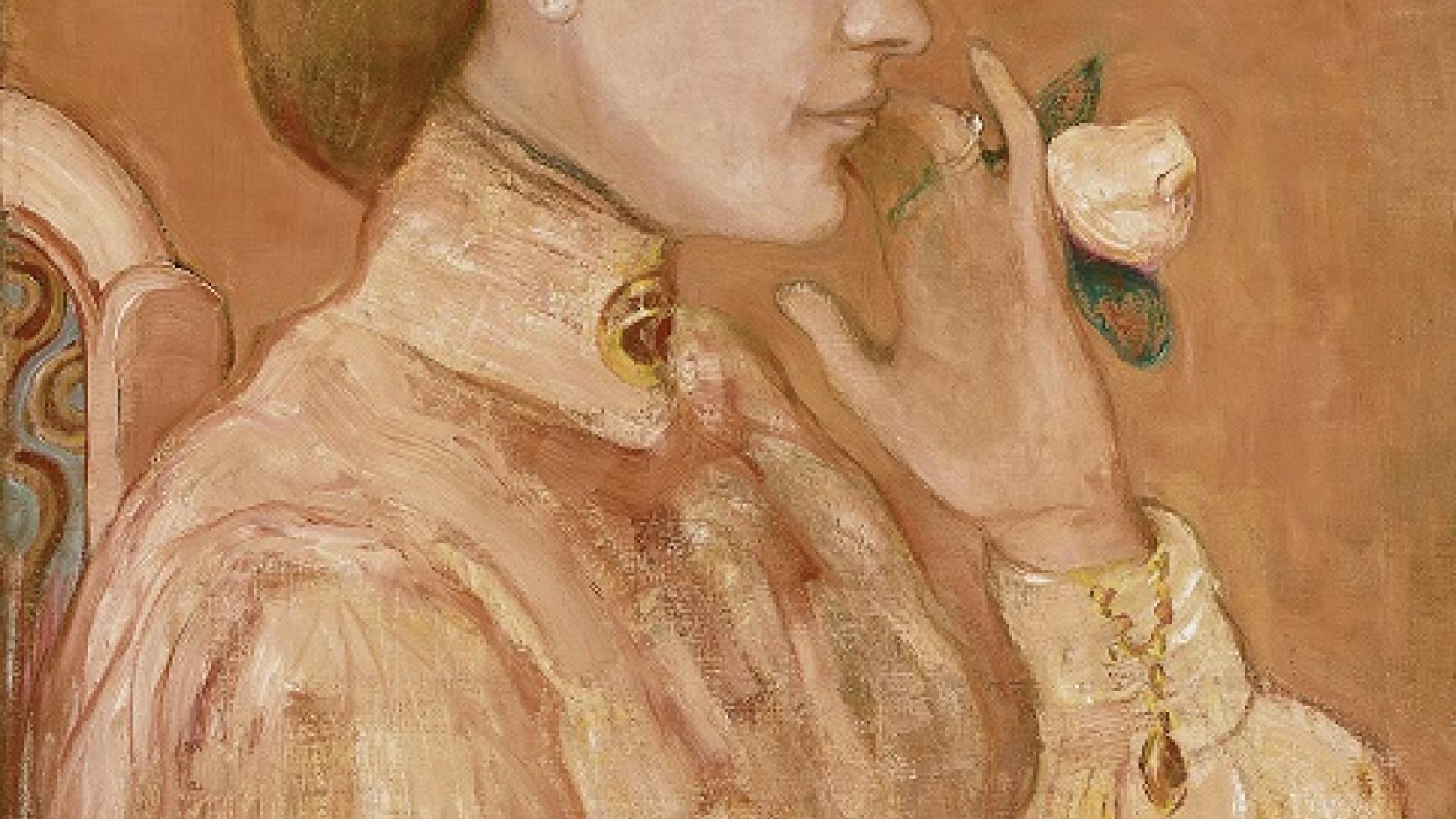

Starting out as a prodigy, the young artist drew on Art Nouveau symbolism and the Pre-Raphaelite ideals, the cladding of the English imagination in the cloak of Italian Renaissance (see e.g. Woman with Rose, 1904). These helped him to discover what was to become his refuge and the most suitable environment for his artistic way of life, Italy, as well as an alter ego, a fellow exile, Dante (A Song Already Sung of Light and Love, 1904). His distinctive motifs and themes were born early on, with female figures receiving the most important role. It is their amorous forms that emerge from the past, it is their astral presence that turns the world into a garden. Other sources he used extensively during the rest of his career, in addition to the Renaissance, included Flemish Baroque masters (e.g. Isac Van Ostade) and Rococo art (e.g. Antoine Watteau).

However, the lure of the past is no mere citation. Instead of copying, he recreated, even relived, the artistry of the Renaissance, because he liked to put on the costumes of these bygone ages. His relationship to history was, first and foremost, intuitive; he himself called his works “historical intimacies,” in which concealment is as important as exposure—they could be said to have an erotic character. His almost fetishistic adoration for objects and locales with personal histories is the most telling illustration of what Gulácsy sought in the past. Above all, he was looking for narratives for his dreams, amorous, tragic or heroic stories, which he could then inhabit (as in Self-portrait in Renaissance Attire, with Flower, 1903), so as to make reality more colourful.

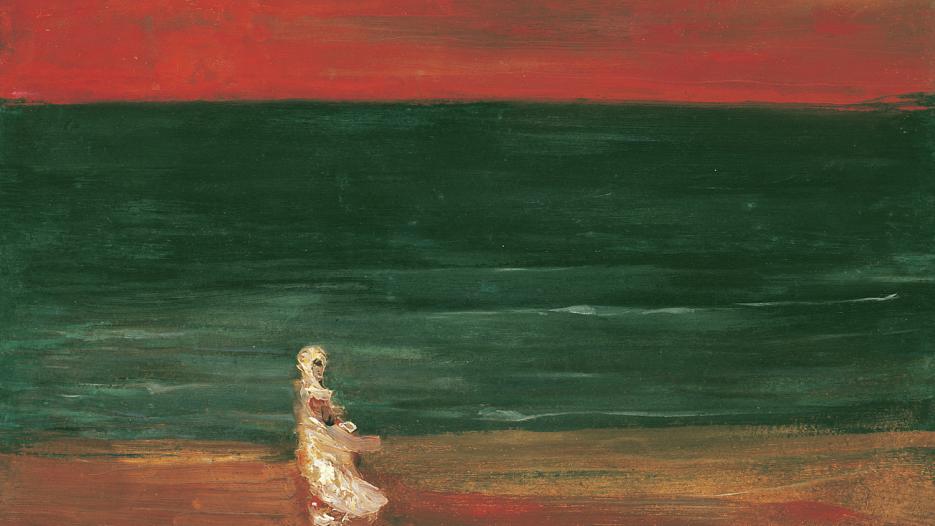

His personal misfortune notwithstanding, Lajos Gulácsy’s oeuvre was no isolated phenomenon. It is very well suited to be a focal point for the study of the turn of the century and the early 20th century, as he both exemplified a productive turn towards the past, and foreshadowed visionary trends in painting. His themes reflect the aestheticism, decadence, cults and fears of his age, while by creating the world of Na’Conxypan, he practiced the poetry of private mythologies. It is fair to say his endeavours established a new trend in modern Hungarian painting, alongside post-Impressionism and the avant-garde, a trend rooted in an Art Nouveau interpretation of the Renaissance, and reaching as far as visionary Surrealism.