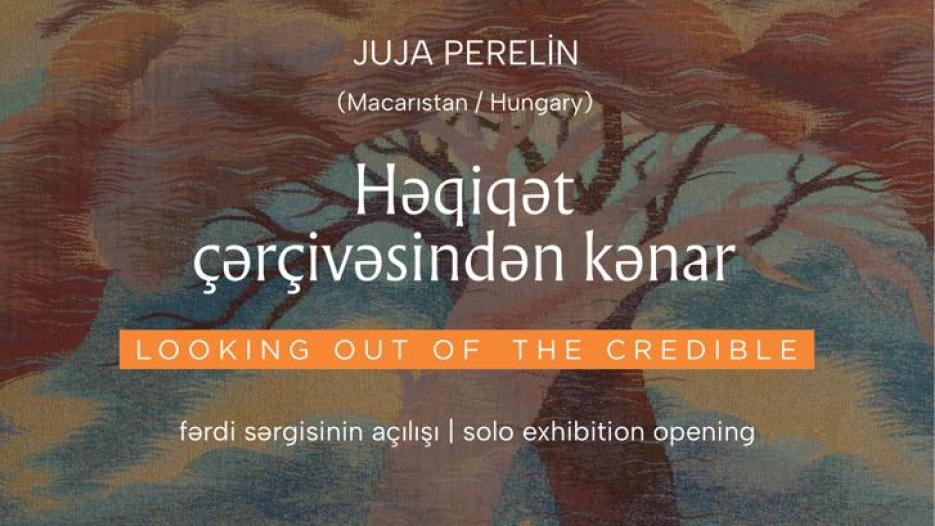

A maker of artworks with relaxed painterliness, Zsuzsa Péreli uses colourful threads, rather than a brush. Expanding the genre of the tapestry, she experiments with new materials, techniques and procedures as she probes into layers of time and memory. She includes ‘found objects’ in her compositions, demonstrating both a respect for tradition and a desire to break the mould. The metaphysical and sacred themes that run through her oeuvre mediate between two worlds, intimating and translating for the viewer all that can only be intuited about non-material reality.

The most beautiful pages in the Hungarian history of the Gobelin, the woven tapestry of the European tradition, are mostly associated with Noémi Ferenczy and Zsuzsa Péreli: the former is considered a founder of the genre in the country, the latter someone who breathed a new life into contemporary tapestry art. She was the first foreign artist to be honoured with a solo exhibition in 2001, in Aubusson, France, the capital of the Gobelin. While she retains the most precious traditions of the genre, she never ceases to push its envelope with original ideas and inventions—while taking care not to break the same envelope.

Finishing a woven tapestry requires advanced specialist knowledge and special artistic sensibilities, a sense of colour, which may explain why so few artists execute their own designs. In this regard, Zsuzsa Péreli has broken with the centuries-old practice that involved cooperation between two or three artists for a single tapestry. Péreli lays great store by making every square inch of the finished work herself, even if it means being tied to the loom for months on end, often for a year, where she works, from sunrise to sunset, on the slowly growing image with the humility of a monk copying manuscripts in a medieval scriptorium.

Hers is a distinctive impressionism, because she does not make cartoons; she usually uses a postcard-sized black-and-white sketch. Since she works on an upright loom, she can see both sides of the tapestry in progress, though never the whole completed part, only a segment of 20 to 30 centimetres. The unity of the complete piece already exists in her mind before she sets to work, and she gradually makes this visible in the long process of weaving. She twists together different yarns to create endless varieties and soft transitions of colour shades, which together, like the notes in a score, create the final colouristic unity of the tapestry.

When she began her career, the art of the tapestry was at a crossroads not only in Hungary but in Europe as well. It seemed to be necessary to enable the genre to express ideas that concern modern man, while retaining the principles of the original technique. Péreli chose to return to the roots and weave her own works. Her respect for the classical traditions, however, did not prevent her from creating – with humour and irony, deep faith and humility – the individual culture of forms, the mode of expression, that marks all her works.