For over a thousand years, Poland, Czechia, Slovakia and Hungary, countries in the centre of the continent, on the boundary between (and often in the buffer zone) of the West and the East, have occupied a special position in the history of European culture. In the course of their history, they were now bastions defending the West against invaders from the East, now acted as a link between the two poles, and in the 20th century they often became the toys of the great powers that divided them, dissolved them or created them. All the while, they strove to maintain their political and economic independence, their national identity and cultural values, and as early as the middle of the 14th century they found, at the Congress of Visegrád, that they can attain their goals together more easily than separately.

Whilst defending their local interests, the Visegrád countries are closely linked to the social, economic and intellectual development of the western part of Europe, and this also holds true of the visual arts. If with some delay, they always sought to draw on the most progressive trends of the time, and to connect to the Western art scene. The same duality, the individual stance of reflecting on global trends, is what lends Central European art its distinctive flavour, its chief value.

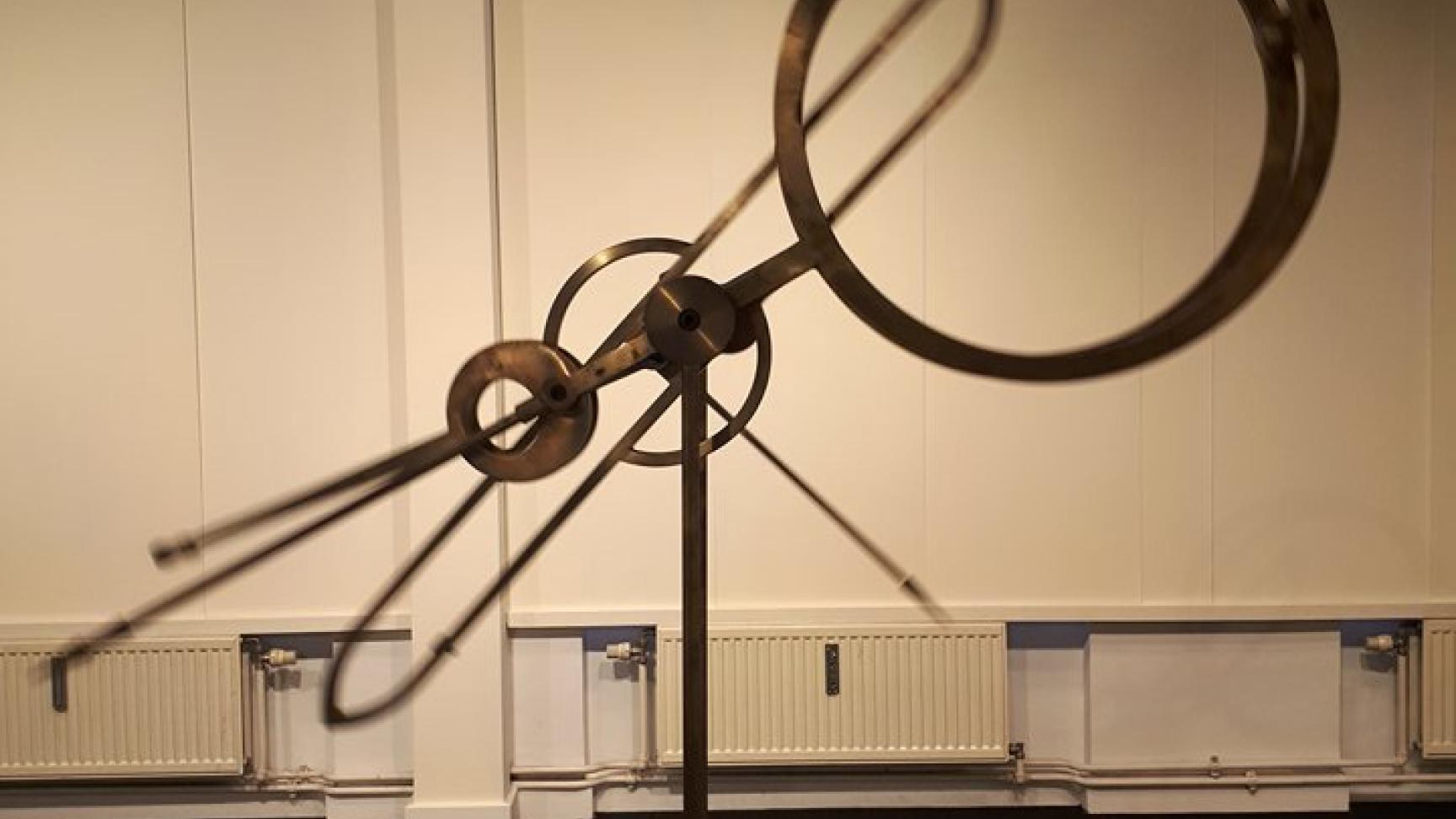

From the 1950s on, the artists of the Visegrád countries were confronted with a challenge greater than ever before, that of keeping their individual and artistic freedom in the face of communist ideology. Artworks often reflected on political events, criticized the regimes openly or covertly, creating what now count as historical documents of those times. Following the political transition and in consequence of such new challenges of the turn of the century as digitalization, globalization and the erosion of existential certainties, art’s emphases shifted to questions like the individual’s role and place in the modern world, the effects of consumerism on traditional values, and the conflicts of individual and collective interests. As they search for answers, contemporary artists do not hesitate to employ new materials and techniques, or to mix traditional materials in a single work, to attain more nuanced expressions of their messages.

Alongside styles that rely for their effect on more concrete, and hence perhaps more accessible, figurative or natural forms (such as surrealism, pop art or hyperrealism), artists readily employ various non-figurative trends’ modes of expression to suggest the complexity or intricacy of the world, or the moods and emotions of the individual. As the geometry-based complex experiments in form so the gestures of lyrical abstraction and its plays with facture communicate intricate signs and emotions, to decode which the viewer must be ready to tackle complex thoughts and to concentrate intensely.

For the same reason, it is a great challenge for the curators to balance their subjective value judgement with the desire to create such an objective overview of Central European art that is truly representative of the outstanding values of contemporary painting, sculpture and graphic art in the four countries, as well as of the similarities and differences between the artists’ ways of thinking, while making this choice selection a lasting cultural experience for a wide spectrum of audiences.